Embedding narratives into the cloth

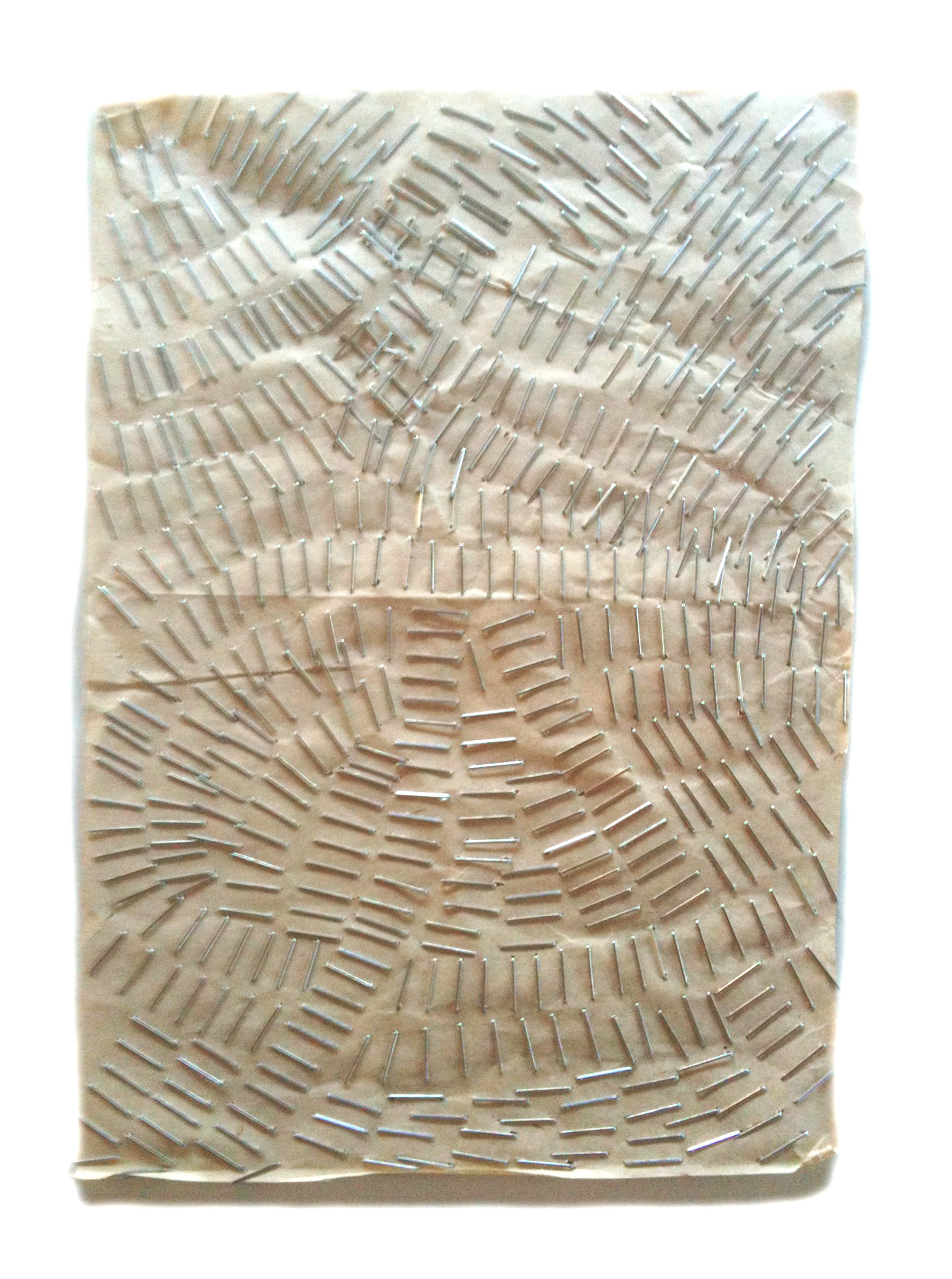

I’m interested in the instability of natural dyes as I think it provides a potent metaphor for the fading of memories. I expect, over time, that the colours will etiolate from the quilt. And I’m okay with that. Embracing this change as a positive is in direct opposition to the priorities of commercial textiles. Any change in colour is seen as an imperfection and a sign to throw the fabric away.

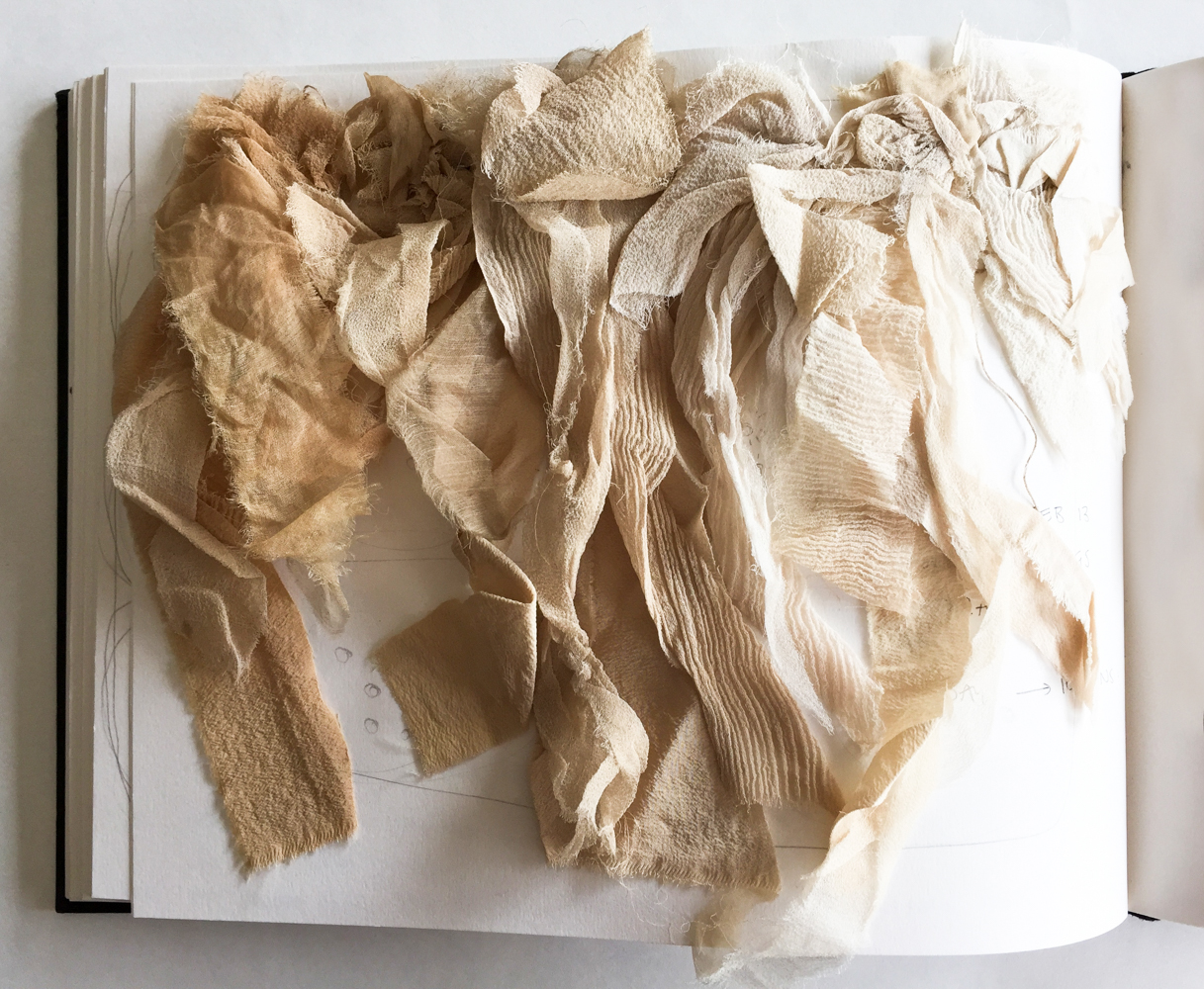

Some of the silks were dyed with memory-charged herbs, such as Rosemary, Bacopa Monnifera, Gotu Kola and Gingko Bilboa. Not all were successful, but I enjoyed experimenting with each one.

I also applied a process of folding, tying and blocking my silk remnants before the dye bath to create un-dyed shapes on the cloth. This gives a sense of the resistance of memory to retain accurate detail from a past experience.

The memory of place, and the potential inaccuracy of this memory, reminds me of a term coined by Duncan Bell (2003) - Mythscape. Bell uses this to describe the ‘temporally and spatially extended discursive realm in which myths of the nation are forged, transmitted, negotiated, and reconstructed constantly.’ I feel I do the same with my memory of emotionally charged places of my childhood - my recollections have become myths over time.

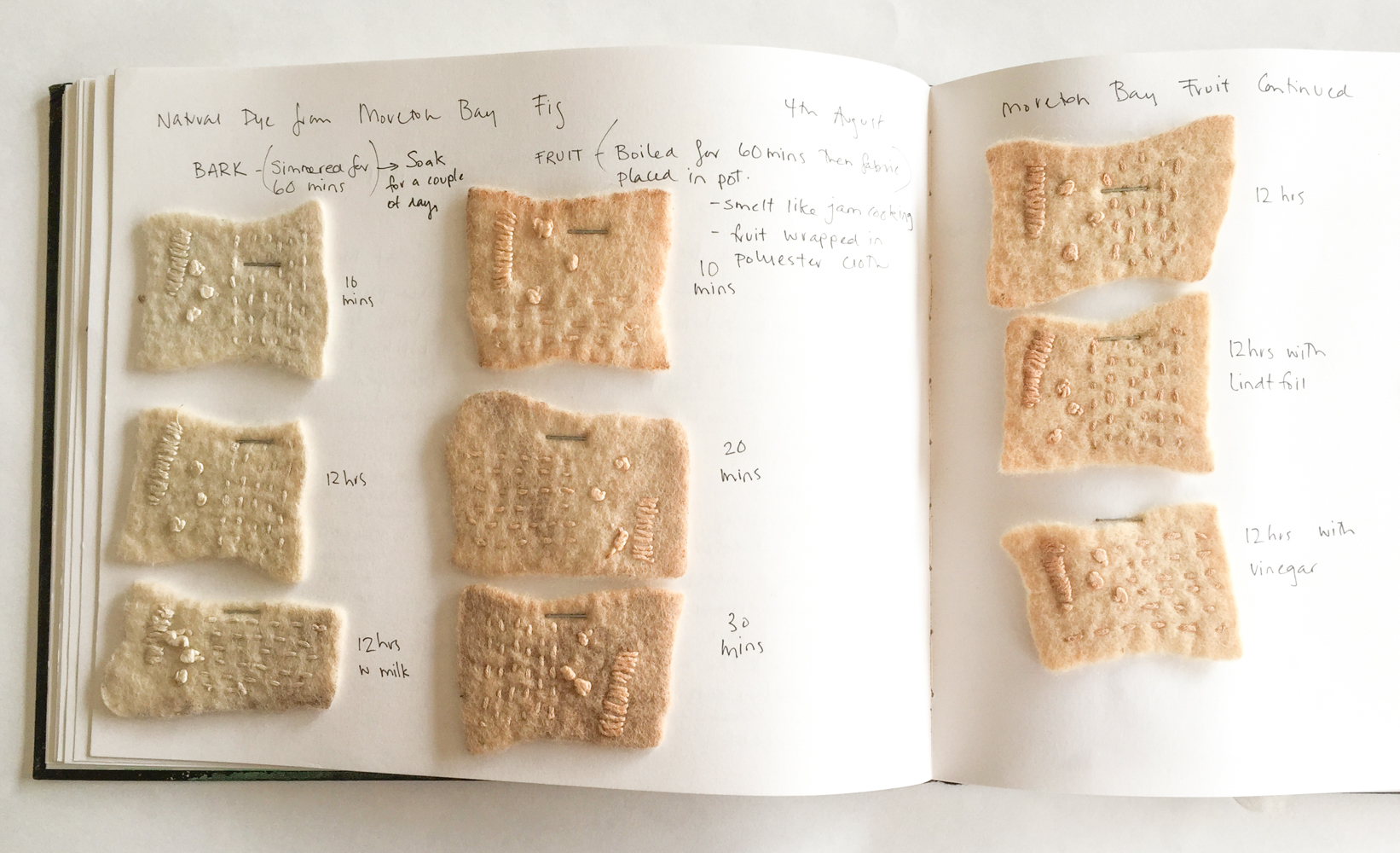

Locating Place

Gathering natural dye sources from my local haunts has ingrained time and place into the quilt. Topology of Memory traverses a childhood past and mixes them with the present. The act of gathering fruit from under Moreton Bay Fig trees recreates the long days adventuring on the family farm, collecting treasures, unaware of time passing, observing the small and the large details of the land. I was pregnant with our first baby while foraging for the figs, so the memory of bending and stooping by the foreshore of Blackwattle Bay with a big belly is strong. It was a physical touching of the land that connected me and the dyed cloth to place.

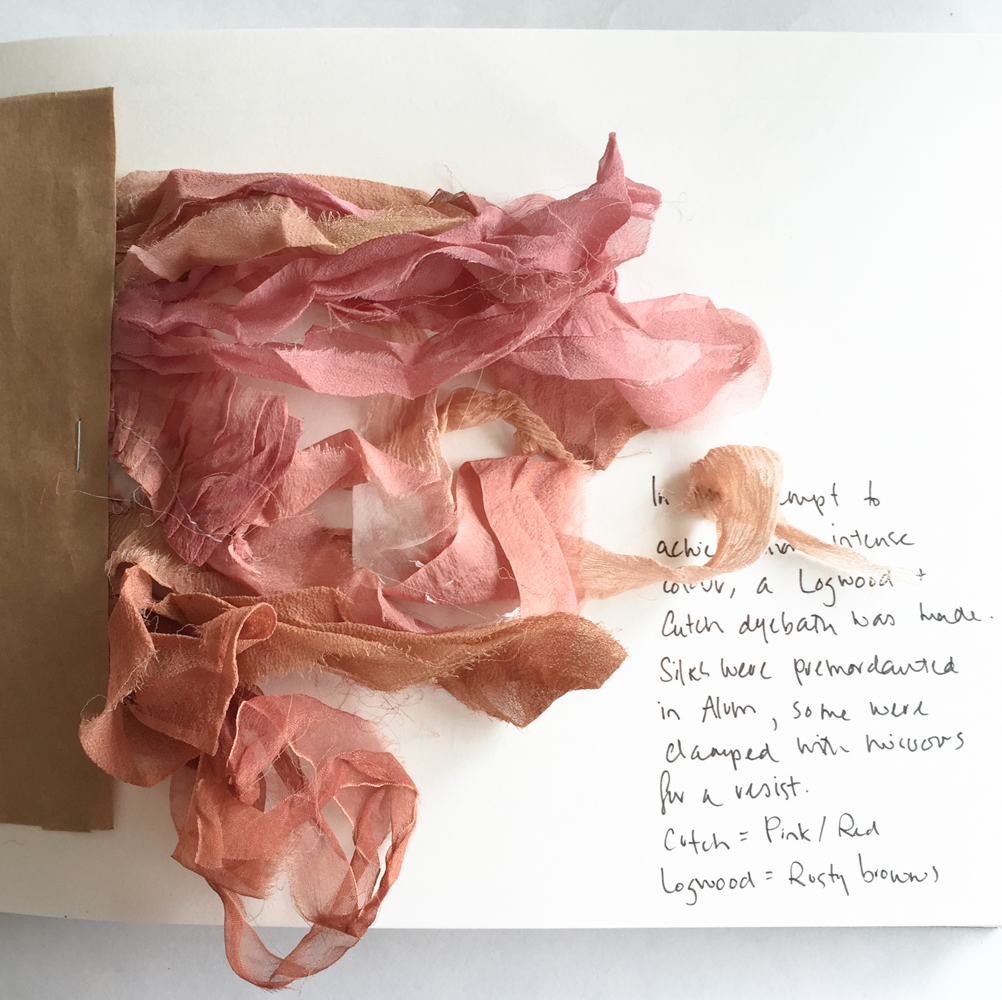

Colour

sometimes it’s just about the colour. Finding the red-dirt hues of the land was important to me and was eventually achieved with a mixture of cutch and logwood. Both were sourced from suppliers rather than my surrounding environment. The different levels of reds were discovered by using a variety of silks, and removing them from the dye pot at different times. The longer they soaked, the stronger their colours. The longer one ponders a memory, does it strengthen in the same way?

Avoiding toxins

And it’s always about avoiding toxins. The effect chemical dyes have on the environment and the human body are numerous. The textile industry has much to answer for in terms of environmental damage in the pursuit long-lasting and commercially stable dyes. Natural dyes still need to be handled with care (and never thrown onto the backyard grass like I once did with dire results) and safety equipment is a priority in terms of skin, respiratory and eye protection. However they offer a much safer and more responsible process of embedding colour into cloth.